I'm really pleased to announce our new paper on "Circles of Support and Personalisation". In it we explore how a new wave of circles of support could enhance people's lives, build community connections and community capital, with examples from some of the work we've seen in Lancashire and around the country.

Circles of Support are really a very simple and informal method of supporting a person's life. They bring people together around the person to think about how their life is working and take action to make it better.

This method means that people's connections in the community are really valued and sought after, and it seeks ways that people can contribute their gifts to the community.

We're hoping to organise a big 'Circles Convention' in Lancashire, where we'll think about how we can build the 'second wave' of circles: so watch this space!

http://www.helensandersonassociates.co.uk/media/75948/circlesofsupportandpersonalisation.pdf

Human Thinking Together

Thursday, 5 July 2012

Friday, 20 April 2012

Ginott's Letter To Teachers

I was listening to a discussion this morning about how someone like Assad, a trained doctor, who has sworn the hippocratic oath, could be capable of such inhumanity toward the Syrian people.

It made me think about the inhumanity displayed every day in our own country against people with disabilities, some deeply vicious inhumanity from people in the form of hate crime, and a mundane and insidious inhumanity from the bureaucracies and systems designed to deliver support to people with disabilities.

I remembered this poem written by Haim Ginott back in 1972, that describes why merely educating people is not enough.

We tend to believee that a good education somehow makes us better people. Certainly in human services there's a very strong culture of valuing people's qualifications. But if those qualifications become a barrier between us and our humanity, then something is going wrong.

What helps us become more human? How do we prevent ourselves from being well educated, highly efficient agents of dehumanisation?

It made me think about the inhumanity displayed every day in our own country against people with disabilities, some deeply vicious inhumanity from people in the form of hate crime, and a mundane and insidious inhumanity from the bureaucracies and systems designed to deliver support to people with disabilities.

I remembered this poem written by Haim Ginott back in 1972, that describes why merely educating people is not enough.

Dear Teacher,

I am a survivor of a concentration camp. My eyes saw what no man should witness:

Gas chambers built by learned engineers.

Children poisoned by educated physicians.

Infants killed by trained nurses.

Women and babies shot and burned by high school and college graduates.

So I am suspicious of education. My request is: Help your students become human. Your efforts must never produce learned monsters, skilled psychopaths, educated Eichmanns.

Reading, writing, arithmetic are important only if they serve to make our children more human.

I am a survivor of a concentration camp. My eyes saw what no man should witness:

Gas chambers built by learned engineers.

Children poisoned by educated physicians.

Infants killed by trained nurses.

Women and babies shot and burned by high school and college graduates.

So I am suspicious of education. My request is: Help your students become human. Your efforts must never produce learned monsters, skilled psychopaths, educated Eichmanns.

Reading, writing, arithmetic are important only if they serve to make our children more human.

We tend to believee that a good education somehow makes us better people. Certainly in human services there's a very strong culture of valuing people's qualifications. But if those qualifications become a barrier between us and our humanity, then something is going wrong.

What helps us become more human? How do we prevent ourselves from being well educated, highly efficient agents of dehumanisation?

Thursday, 19 April 2012

Ground Rules for Person Centred Thinking and Planning

|

| Linkability's Person Centred Planning Task Group wrote these ground rules for their meetings |

One set of things to establish early with the person is exactly WHO will be involved, (and often also who won't be involved) which will usually be determined by the purpose of the planning. It's important that we're clear with the person about how we're going to keep them involved or informed about those conversations. We also establish whether any particular topics are 'off limits', or need to be thought about at a different place, perhaps with a different set of people.

There are also rules that can determine how the meeting will be conducted. Often the participants will generate these themselves, but facilitators often have a few rules up their sleeves that they might seek the person and the group's agreement to.

Agreeing a set of ground rules is also a kind of ritual that separates the planning session and planning space from the concerns of normal everyday life. They're a way of saying 'for the next hour or so, we're going to focus solely on the work of thinking together with this person, in a way that requires our careful and mindful attention'. They also make sure that people feel safe and orientated within this space, they understand what is expected behaviour. They're also a summary of the key skills involved in person centred work. It's no accident that the first 3 rules all relate to listening well and welcoming diverging viewpoints in a way that makes sense to all involved.

The rules belong to the whole group, and the whole group has permission to invoke and use them. The person they apply to most of all is the facilitator of the group. They must embody the rules because if they don't follow them, then nobody will.

Here's a short list of possible group ground rules, then an explanation of why those rules are there:

Everyone’s views are welcome.

Listen with respect.

No Jargon

Speak from the heart

No fixing

No obsessing/5 minute rule

Inperfect spelling is OK

Do what you need to do to be here/misery is optional

We believe everyone’s views are welcome because the person and everyone who knows and cares about the person and has been invited to participate can impart valuable knowledge that will help us support that person better.

It’s necessary to listen with respect because this is how we make sure that everyone’s views are welcomed. We’ve learned that good listening that gives people time to think helps people think and express themselves better

Jargon is banned because it’s a way that one group of people can maintain power over another. It’s a private language that excludes the person, their family and frontline staff from the discourse. It can be used as camouflage for deep ignorance. If you really understand a concept, you should be able to explain it in everyday English.

We ask people to speak from the heart as well as the head because Person Centred Thinking deals with the world of feelings and emotions as much as the world of facts. We want people in the meeting to feel able to express their emotions so that this is a real discussion about someone’s life, not just a business transaction.

No fixing. We’re not here to ‘fix’ the person, we must ‘accept the person, change the situation’. Nor do we wish to jump quickly to the easiest and most obvious solution. Sometimes spending a bit more time gathering information and defining the problem will help us find actions that are far more creative and productive.

We don’t want to get obsessed with a small detail, or spend more than 5 minutes discussing issues that the people in the room can do nothing about. If we do get stuck on issues like this, anyone can invoke the ‘5 minute rule’, the facilitator can write the issue down, so that it can be taken to the people who CAN do something about it.

Person centred work is not a spelling test. We need all that rich person centred information that’s in people’s heads. So inperfect spelling is OK.

Misery is optional, We want everyone to feel comfortable during our work! If something’s making you uncomfortable, do something about it!

What ground rules do you use in your own person centred planning?

Tuesday, 20 December 2011

Conflict in Planning

Over the last few years I've been involved in work thinking about the conflicts that sometimes occur during person centred thinking and planning.

It's no secret that human beings, even when they're motivated by their highest purposes will often come into conflict with each other. It's fundamental to who we are. It's neccessary. Trying to avoid conflict is like trying to avoid gravity.

When we're engaged in the work of personalisation and person-centred change, conflict is even more likely. Introducing change that shifts power in the direction of the person and the people closest to the person requires change to easy habits, it requires change to complacent thinking, it requires change in structures, customs and practices. It requires people in positions of power to examine the impact that the exercise of that power has on individuals. It creates discomfort, stirs up the millpond, challenges assumptions, opens up closed cultures to scrutiny by people who use services and their allies.

There's a saying that when everyone is thinking the same thing, it's a sign that no real thinking is occuring. If person centred work is not creating conflicts, then we're probably not doing it right.

Add to this mix the impact of a rising number of people requiring social care, coupled with increasingly limited resources being allocated to meet this need. This forces us to fight over slices of a cake that's getting smaller, when maybe we should be thinking about how we take over the bakery.

However we live in a culture where we see conflict as something to be feared. We don't develop conflict skills. We therefore respond to everyday conflict in one of two ways. We either avoid it, meaning that issues fester and grow, or we lash out fearfully, engaging in conflict in a way that is damaging to ourselves and others. I think it's therefore worthwhile thinking more about conflict and ways of engaging in it that keep ourselves and others as safe as possible.

I deliver a conflict training. People keep calling it 'conflict resolution'. I keep telling them that it's not a conflict resolution training because I believe that it’s not always possible, necessary or even desirable to resolve every conflict and disagreement that occurs during person centred planning and thinking.

What is sometimes possible is to use the energy that the conflict generates as a means of motivating people to think harder, take action and learn, whether or not the conflict is ever ultimately resolved.

The impossible desire to ‘resolve’ every conflict emerges from the myths of professional infallibility and service perfection. The reality of everyday life is working with people while agreeing to disagree on many issues, if we can use the exploration of those disagreements to generate positive change, and prevent them descending into negative and destructive forms of conflict, then we are moving in the right direction.

I'll be blogging much more on this topic in future weeks: I intend to discuss how we can help people understand that conflict can sometimes be positive, about ways of turning negative conflict into positive conflict, about how we ensure that all points of view are heard and recorded during conflict, how we can use mindfulness in conflict, and how appreciation can enable people who disagree to honestly recognise and honour each others' gifts and heartfelt motivations.

Let's see conflict in a similar way to how we see fire: something to be dealt with carefully, treated with respect, something that is notoriously dangerous when out of control, yet is essential to our lives and potentially a massively productive and creative force.

It's no secret that human beings, even when they're motivated by their highest purposes will often come into conflict with each other. It's fundamental to who we are. It's neccessary. Trying to avoid conflict is like trying to avoid gravity.

When we're engaged in the work of personalisation and person-centred change, conflict is even more likely. Introducing change that shifts power in the direction of the person and the people closest to the person requires change to easy habits, it requires change to complacent thinking, it requires change in structures, customs and practices. It requires people in positions of power to examine the impact that the exercise of that power has on individuals. It creates discomfort, stirs up the millpond, challenges assumptions, opens up closed cultures to scrutiny by people who use services and their allies.

| Image from http://isathreadsoflife.wordpress.com/ “Fire drives us out of ourselves, it touches the spark within us that leads us to create new worlds in the face of the years gone to ashes before us” |

Add to this mix the impact of a rising number of people requiring social care, coupled with increasingly limited resources being allocated to meet this need. This forces us to fight over slices of a cake that's getting smaller, when maybe we should be thinking about how we take over the bakery.

However we live in a culture where we see conflict as something to be feared. We don't develop conflict skills. We therefore respond to everyday conflict in one of two ways. We either avoid it, meaning that issues fester and grow, or we lash out fearfully, engaging in conflict in a way that is damaging to ourselves and others. I think it's therefore worthwhile thinking more about conflict and ways of engaging in it that keep ourselves and others as safe as possible.

I deliver a conflict training. People keep calling it 'conflict resolution'. I keep telling them that it's not a conflict resolution training because I believe that it’s not always possible, necessary or even desirable to resolve every conflict and disagreement that occurs during person centred planning and thinking.

What is sometimes possible is to use the energy that the conflict generates as a means of motivating people to think harder, take action and learn, whether or not the conflict is ever ultimately resolved.

The impossible desire to ‘resolve’ every conflict emerges from the myths of professional infallibility and service perfection. The reality of everyday life is working with people while agreeing to disagree on many issues, if we can use the exploration of those disagreements to generate positive change, and prevent them descending into negative and destructive forms of conflict, then we are moving in the right direction.

When we're facilitating person centred thinking, we’re not aiming to get everyone to agree, we’re aiming to help the person move toward a life that makes sense for them, and to make our services responsive enough to enable this for many people – some disagreements can hold this back, others help us think better and motivate us to act. We’re simply aiming to have more of the latter kind of disagreement! We therefore need to consider what conditions, what questions and methods help us manage conflict more productively.

I'll be blogging much more on this topic in future weeks: I intend to discuss how we can help people understand that conflict can sometimes be positive, about ways of turning negative conflict into positive conflict, about how we ensure that all points of view are heard and recorded during conflict, how we can use mindfulness in conflict, and how appreciation can enable people who disagree to honestly recognise and honour each others' gifts and heartfelt motivations.

Let's see conflict in a similar way to how we see fire: something to be dealt with carefully, treated with respect, something that is notoriously dangerous when out of control, yet is essential to our lives and potentially a massively productive and creative force.

Tuesday, 13 December 2011

What Does it Take To Train People in Person Centred Thinking?

If you’re going to take that step of standing up and teaching person centred approaches to others, then It's obvious that you need to know and understand how to use the person centred skills and tools you wish to teach.

To me it's also obvious that you must have a deep commitment to the values the underpin person centred approaches, you must also be hungry to learn more, and be eager to share what you learn with others, so that more people can be supported better to build better lives, with valued social roles in their community.

Background knowledge of the social model of disability, of Social Role Valorisation theory, of the five accomplishments, of capacity thinking will give a trainer good grounding. Your thirst for further knowledge will help you learn these things if you don't know them already.

Without doubt, you'll need good mentorship from an experienced trainer, and be able to use every opportunity you can to explore the art of planning and training with others who belong to the community of person centred practitioners, a warm, welcoming community that will appreciate what you bring to it.

But when it comes to standing in front of a group of learners, it's much less a matter of what you know, than about how you help others dig out what they ALREADY know. You must almost forget what you know, and instead work on creating conditions where people lead their own learning, where deeper learning can happen.

But when it comes to standing in front of a group of learners, it's much less a matter of what you know, than about how you help others dig out what they ALREADY know. You must almost forget what you know, and instead work on creating conditions where people lead their own learning, where deeper learning can happen.

Because you're stood up at the front, people will wish to see you as the expert, but person centred thinking is trying to demolish the view that some people are ‘experts’, and that everything must go through the experts in order to be valid. We are trying to build instead the view that everyone has knowledge that is based on their own experience and their own lives, and has the capacity to learn more. The right questions asked in the right way can help bring this knowledge to the surface, and help focus people’s attention onto what they still need to learn for themselves.

This is the trainers’ job: to help people and groups rediscover the knowledge they already have, and stimulate the curiosity to learn more. This is also what person centred thinking aims for. Person Centred Thinking tools are really tools that help people and groups rediscover what they already know, or open them up to seeking for what they don’t yet know.

Therefore in order to train person centred thinking, it’s necessary to train in a person centred way. More important than how you speak and what you say is what happens in the gaps in between: How you LISTEN, how you give people time to THINK, the RESPECT that you show to learners, the gifts they bring with them and the feelings that training evokes.

Poor trainers stand in front of a powerpoint and talk and talk, and talk, and talk...

Good trainers ask questions that stimulate discussion, use techniques that give everyone a chance to think and speak and open themselves up to listen well to everything that the group is saying, with their words and with their whole selves. People learn far more when they voice what they’re learning, and listen to and help each other. Good trainers don't talk for the sake of filling up silences. They don't fear silence. They use silences as a tool, a space where people can think and be together, a space for learners to fill with their own learning.

People learn person centred approaches by immersing themselves in person centred work, not by watching a powerpoint: Conducting an experiential exercise, then discussing the learning from it is the beginning of this, as people use themselves as their own ‘focus person’. Time should be balanced so that 20% is explanation, 80% exploration.

Your learners will know far more than you do about their own work situations and about themselves. Respect this, bring it out. Your job is to ask the questions that will help people allow this deeply stored knowledge to spout upward from their own internal wells, so that it can be pooled and swum in. If you’re doing this right, you will learn just as much as your learners do from a training session. With such deep wells already there, there’s no need for you to be the fountain of all knowledge, learners are not empty vessels, they are full to the brim.

Finn McCool and the Salmon of Knowledge

It was said that Fintann the bradán feasa or Salmon of wisdom, had swum in the well of knowledge, and eaten nine hazel nuts that fell into the well from the nine hazel trees that grew around it, and that therefore this salmon contained all the wisdom in the world. Moreover, it was said that whoever could catch and eat this salmon would in turn, know all there was to be known.

Finally Finegas hooked the magic and immortal fish. He was keen to consume it's flesh, know everything, and thus become the greatest teacher there had ever been.

"Start a fire and cook this fish Finn!, but whatever you do, don't eat it, it's mine!" said Finegas.

Finn loyally did as he was told, but when the fish got really hot, fat started spitting out of it, and a sizzling hot drop landed on his thumb. Without thinking, Finn put his thumb into his mouth to sooth it. All the precious knowledge in the salmon was focussed into that little drop of fat, and wham! now it was inside Finn.

When Finegas got back he could see Finn had changed, his eyes were sparkling with experience and wisdom. Finn explained what had happened.

"Finish eating the salmon" said Finegas "It's you who is destined to know, not me".

After that, Finn became the wisest of all leaders. Whenever he was presented with a problem, he would simply suck his thumb, and know exactly what to do.

Friday, 9 December 2011

Book Review: Conversations On Citizenship and Person Centred Work

“The more deeply this whole group can listen, the more strongly they believe in the person, the more vividly they can imagine possibilities, the more widely they are connected, the more creatively they can see ways to move forward, the more courageously they can enter into agreements that engage their integrity, the more likely cycles of planning and action will generate good changes.” O'Brien p22

In her introduction, Blessing asks why, despite all the great thinking, theorising and training that’s been carried out over the last decades, often only language has changed, with human service delivery systems and ‘experts’ still acting as the commonly accepted gatekeepers to community.

In an attempt to redress this disconnection between people and their communities, the book draws together ideas from some of the most inspirational thinkers from a variety of areas, the person centred planning and thinking of people like Beth Mount, Jack Pearpoint and Michael Smull, the positive potential of appreciative inquiry summed up by Diana Whitney, the value of developing communities based on their assets, recounted by Mike Green, and work enabling people to achieve their potential through employment explored by Denise Bissonnette and Connie Ferrell.

Each of these writers puts forward their ideas, experiences and values in response to a set of incisive questions. This question and answer format is a natural way of simplifying and opening up thinking that goes back to Socrates and Plato, making it much easier to find something to whet the appetite to consume further bitesize morsels of the writers detailed arguments and alternative world views.

Overall the book is like a delightful meal, each thinker bringing their own unique dish to the table, but running through each succulent dish are the common flavours of humanity, community, potential, courage and capacity, meaning that while the book was written to support people on a particular leadership course, the short introductions to appreciative inquiry, asset based community development, person centred thinking and supported employment are both a useful introduction to these areas to the uninitiated, and an inspirational resource to provoke thinking and action in those who are already familiar with these ideas.

The deepest theme of all is that the changes required to genuinely include and value people with disabilities in our society will be accomplished by individual people in their own lives, supported by the people who love and care about them. O’Brien argues that these people will benefit from using person-centred planning as “a means to guide the personal creativity and organisational innovation necessary for people with disabilities to act in valued social roles as contributing citizens” but adds a pinch of salt to the dish with a warning about the limits of Person Centred Planning: he explains that this cannot be treated as “mindless word magic disconnected from a context where people can act resourcefully on what the planning discloses as meaningful”, calling for commitment to building the social contexts where real change can be possible, to supporting the person to convene people who can actively support them to offer their contribution to the community, and to supporting the communities of practice that nurture the applied and relational skills of the people who feel called to support such purposeful convening.

Tuesday, 6 December 2011

Five Ways of Thinking

Five methods of thinking.

Are you always running up against the same problem?

Maybe thinking about it in a different way might help. Maybe we get trapped in one or two particular methods of thinking that have been productive for us in the past, but which now seem to have run dry.

The world's greatest thinkers recognise that trap. Einstein said "We can't solve problems using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them".

One of the skills of facilitating is to help a group raise it's thinking, exploring zones of mindfulness, stimulating and challenging the imagination, and enabling people to plan together with intention.

Which approaches harvest the bounty of our common sense?

What approaches help us gather the evidence we need to make rational decisions?

What approaches help us gather the evidence we need to make rational decisions?

What practices help us develop mindfulness and deep awareness of ourselves and our situations?

What questions tease us and provoke our imaginations?

What sustains us to think together, plan and live with intention?

Trees, true-divining trees,

Discover all your poet asks

Drumming on his brow. "

Robert Graves

Monday, 5 December 2011

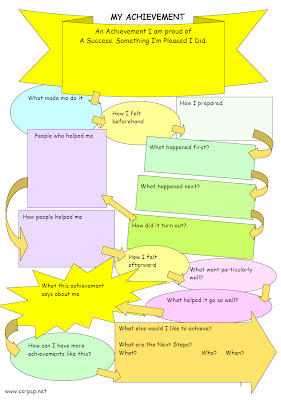

Learning From Achievements

One of the most crucial and fundamental elements of Person Centred Thinking is a deep listening for a person's capacities and potential. One tool that can tell us so much about our capacities, and what we can achieve when we are at our best is the achievement tool, a tool that combines ideas taken from appreciative inquiry (AI), from person centred thinking, and from capacity thinking.

The achievement tool has a few purposes.

The first is simply to make a record of something that we're very proud to have accomplished.

The second is to celebrate that accomplishment.

I realised how powerful this tool was the very first time I used it with a group. Several members of the group were shedding tears as they told their achievement stories. The whole group felt we were entering important and fertile territory for inquiry, and were able to express so much appreciation for each person after they had told their story. As each story unfolded, the energy in the room grew increasingly hopeful and postive, people left feeling genuine connection with each other and a sense of personal empowerment.

Talking about our achievements is not always easy for people from the English culture. We don't like to 'blow our own trumpets'. But when we do, we go very deep into who we are, what drives us, some of our very deepest feelings.

Appreciative Inquiry is based on the idea that what we inquire into expands. If we inquire into a person's faults and deficits, we will continue to find more and more, until the picture we have painted of them becomes positively debilitating. If we inquire into a person's achievements, we learn more and more about what helps that person achieve, and potentially enable that person to achieve more and more.

The Achievement Tool links directly to other person centred thinking tools.

For example, the question 'What made me do it?' links directly to what is most important to us.

Sometimes people use the tool to tell stories of how they have overcome adversity such as leaving a long term partner, or overcoming a situation that has been thrust upon them. Sometimes it is an achievement of something that they have chosen to attempt. In either case it can help us understand our own key priorities.

'People who helped me' helps us learn more about our real circle of support: the people who are around when we are achieving things, rather than the people who somehow hold us back.

'How people helped me' and 'What helped it go so well?' give us clues about what makes good support for us. If we can recreate the conditions that existed last time we achieved something great, perhaps we can go on to achieve more!

'What this achievement says about me' explores the capacities that the achievement reveals within us. I like to call it like and admire, but with an evidence base.

There's a number of ways to use the tool. It can be used with individuals, teams and even with whole organisations. Even if the only achievement your team can think of is that they organised a really good leaving do for a colleague, the learning from that can give clues about talents and skills within the team that could be applied to the core work of the organisation.

I tend to start by asking everyone in a group to think of something they have achieved. It could be big or small, and I point out that this is not an 'achievement competition'. We can often learn just as much useful information from a small achievement like baking a cake as we do from a major life-changing achievement.

When everyone has mentioned what their achievement is, I ask for volunteers to explore their achievement more deeply. It works to split people into groups of 3, one person to talk more about their achievement, one to ask them questions, and one to record the answers in a way that makes sense.

When people have recorded their achievement, they go back to the whole group and are helped to recount their achievement story. Each story ends with a round where everyone in the group tells the person what they appreciate about them and their achievement.

It's a great way to end a training session so that everyone feels on a high, ready to go out and achieve more!

A lot of organisations are finding it hard to talk to social care commissioners in the language of outcomes, rather than inputs. Using the achievement tool with people we support gives us a real picture of what people feel are the real achievements and outcomes in their own lives. People have used the tool to describe how they gave up smoking, how they recruited their own staff members, how they made new friends, how they used a train independently for the first time.

Teams have used the tool to celebrate winning new tenders, supporting a person to successfully lose weight, in a way that made sense to them, and helping a person whose previous support arrangements had repeatedly broken down to build a successful life in the community.

Here's what Amanda George thinks of the Achievement Tool.

What achievements do you feel proud of? Have you explored what motivated you, and helped you accomplish them? What else could you achieve if you really paid attention to what helps you be at your strongest and best?

The achievement tool has a few purposes.

The first is simply to make a record of something that we're very proud to have accomplished.

The second is to celebrate that accomplishment.

|

| Our achievements tell us so much about ourselves. To find out more about the Achievement Tool, pleas click on the picture. |

The third is to draw out learning from what we have achieved: learning about what it is that helps us achieve.

I've used this tool many times over the last few years since I first designed it in a burst of creativity stimulated by Gill Bailey and Helen Sanderson's training, and by my own research into AI.I realised how powerful this tool was the very first time I used it with a group. Several members of the group were shedding tears as they told their achievement stories. The whole group felt we were entering important and fertile territory for inquiry, and were able to express so much appreciation for each person after they had told their story. As each story unfolded, the energy in the room grew increasingly hopeful and postive, people left feeling genuine connection with each other and a sense of personal empowerment.

Talking about our achievements is not always easy for people from the English culture. We don't like to 'blow our own trumpets'. But when we do, we go very deep into who we are, what drives us, some of our very deepest feelings.

Appreciative Inquiry is based on the idea that what we inquire into expands. If we inquire into a person's faults and deficits, we will continue to find more and more, until the picture we have painted of them becomes positively debilitating. If we inquire into a person's achievements, we learn more and more about what helps that person achieve, and potentially enable that person to achieve more and more.

The Achievement Tool links directly to other person centred thinking tools.

For example, the question 'What made me do it?' links directly to what is most important to us.

Sometimes people use the tool to tell stories of how they have overcome adversity such as leaving a long term partner, or overcoming a situation that has been thrust upon them. Sometimes it is an achievement of something that they have chosen to attempt. In either case it can help us understand our own key priorities.

'People who helped me' helps us learn more about our real circle of support: the people who are around when we are achieving things, rather than the people who somehow hold us back.

'How people helped me' and 'What helped it go so well?' give us clues about what makes good support for us. If we can recreate the conditions that existed last time we achieved something great, perhaps we can go on to achieve more!

'What this achievement says about me' explores the capacities that the achievement reveals within us. I like to call it like and admire, but with an evidence base.

There's a number of ways to use the tool. It can be used with individuals, teams and even with whole organisations. Even if the only achievement your team can think of is that they organised a really good leaving do for a colleague, the learning from that can give clues about talents and skills within the team that could be applied to the core work of the organisation.

I tend to start by asking everyone in a group to think of something they have achieved. It could be big or small, and I point out that this is not an 'achievement competition'. We can often learn just as much useful information from a small achievement like baking a cake as we do from a major life-changing achievement.

When everyone has mentioned what their achievement is, I ask for volunteers to explore their achievement more deeply. It works to split people into groups of 3, one person to talk more about their achievement, one to ask them questions, and one to record the answers in a way that makes sense.

When people have recorded their achievement, they go back to the whole group and are helped to recount their achievement story. Each story ends with a round where everyone in the group tells the person what they appreciate about them and their achievement.

It's a great way to end a training session so that everyone feels on a high, ready to go out and achieve more!

A lot of organisations are finding it hard to talk to social care commissioners in the language of outcomes, rather than inputs. Using the achievement tool with people we support gives us a real picture of what people feel are the real achievements and outcomes in their own lives. People have used the tool to describe how they gave up smoking, how they recruited their own staff members, how they made new friends, how they used a train independently for the first time.

Teams have used the tool to celebrate winning new tenders, supporting a person to successfully lose weight, in a way that made sense to them, and helping a person whose previous support arrangements had repeatedly broken down to build a successful life in the community.

Here's what Amanda George thinks of the Achievement Tool.

What achievements do you feel proud of? Have you explored what motivated you, and helped you accomplish them? What else could you achieve if you really paid attention to what helps you be at your strongest and best?

Thursday, 27 October 2011

The Pictures We Paint

I've been thinking further about the issues I raised in 'The Poet Doesn't Invent, He Listens"

In that post I tried to explain the importance of listening well, and of being accurate and respectful in how we reflect that listening.

I illustrated that post with this picture by Jean Cocteau: "Beauty and the Beast", and promised to talk further about some of the questions it evokes in me.

I illustrated that post with this picture by Jean Cocteau: "Beauty and the Beast", and promised to talk further about some of the questions it evokes in me.

I think it's interesting that Cocteau places himself in his picture, engaged in the act of painting, as well as the sitter, and even the person viewing the picture. I think he's arguing that every picture reflects the artist as much as it does the subject - the portrait is something that has been co-produced by the painter and the painted, and also by the person who is viewing the portrait because of the interpretation they bring to the image.

In that post I tried to explain the importance of listening well, and of being accurate and respectful in how we reflect that listening.

It's a powerful and quite disturbing picture. Many people violently dislike it, others find it intriguing. I think part of Cocteau's intention behind the image was an attempt to illustrate his maxim that "artists make beautiful things ugly".

What I'm getting to, is the point that people who work in health and social care services routinely paint pictures of the people we support too. These pictures are given all kinds of names like "assessments", "pen pictures", "incident reports" "support plans" and "care plans". The brushstrokes such pictures use tend to be devaluing labels and diagnoses, and while art is about capturing both light and shade, such pictures all too often focus entirely on the negative aspects of people's lives. Their weaknesses, their inabilities, their needs, their challenging behaviours. They fail to capture key aspects of who the person actually is to the people that love and care about that person. It's as if the artist instructed by Cromwell to paint him 'warts and all' had just painted the warts. They thus make beautiful things ugly with all the routine banality of bureaucratic paperwork.

The language we use about people reflects deep assumptions. We brand people as 'service users', a term that reflects their role as consumers of services and resources, but ignores their role as potential and actual contributors to society.

There's a theory that what we inquire into expands. The harder we search for faults and inadequacies in ourselves and each other, the more we find. The reverse of this is to inquire into people's gifts, strengths and virtues, what people like and admire about that person. By mindfully searching for these, we can also help other people find them, and see the person in ways that they might not have managed to before.

There's a theory that what we inquire into expands. The harder we search for faults and inadequacies in ourselves and each other, the more we find. The reverse of this is to inquire into people's gifts, strengths and virtues, what people like and admire about that person. By mindfully searching for these, we can also help other people find them, and see the person in ways that they might not have managed to before.

I think it's interesting that Cocteau places himself in his picture, engaged in the act of painting, as well as the sitter, and even the person viewing the picture. I think he's arguing that every picture reflects the artist as much as it does the subject - the portrait is something that has been co-produced by the painter and the painted, and also by the person who is viewing the portrait because of the interpretation they bring to the image.

John O'Brien made a similar point in one of the trainings I was privileged to attend. He mentioned the tendency for person centred plans to reflect aspects of the person facilitating them, plans facilitated by a particular person might focus much more tightly on getting a person into paid employment, reflecting the importance that that particular facilitator attaches to employment, without any conscious direction by the facilitator. 'What do you think of that?' John asked. It's hard to give an answer, it seems like just something that happens, but it must be welcomed if a passion to find some of the potential and capacity that exists in a person helps overcome a little of the underestimation that has been built into every previous picture we've painted of that person.

| Cromwell demanded that he be painted 'Warts and All' What if the artist had only painted the warts? |

People who aspire to person-centredness in their practice therefore need to think about the pictures we are painting of people with our own words, and the techniques we are using to create those pictures. We need to ask, "Who is this picture for?", "What aspects of the person do we wish to discover?", "can we discover this person's gifts and strengths and lay them out for others to find?" It does not mean ignoring people's support needs, it means searching for what makes the best support, support that enhances people's gifts, that matches up with what is important to them, that reflects the direction they aspire to in their lives.

When we go back to the reports that were written about people 20, 30 or 40 years ago we wince at the language and the devaluing assumptions that riddle these outdated portraits and dread to imagine the grey and restricted institutional lives these descriptions condemned people to. We pass judgement on the people that wrote them, forgetting that they were simply reflecting the training they received and the values that motivated services at that time. How do the words we use impact on the lives of people we support today? How will the plans and descriptions we're writing with people now reflect on us in years to come?

Tuesday, 25 October 2011

7 Billion Hearts

According to some statisticians, the world's human population will reach 7billion on October 31st 2011. Others suggest it will be March 2012, but both are really the boldest estimates based on the flimsiest of guesswork.

It's been suggested that the rise in the human population is a big problem, a whole host of neo-Malthusians are lining up to suggest that this many people inhabiting our globe can only be a bad thing, to demand programmes of 'humane population control' and to suppress this human urge to procreate ourselves.

We must not confuse a wish to get rid of poverty with a wish to get rid of the poor. We need to reject a fearful view of our own species. Trying to artificially supress reproduction is deeply damaging to society, as the experience of India and it's transistor radios, or China and it's one child programme shows anyone who cares to look.

Despite the scaremongering, there are ample world resources, if we're prepared to think together of ways to use them less wastefully and more efficiently and fairly, and in tune with our environment.

Every human being is another set of hands ready to work productively for our world community, and our productivity has gone up at least 11 fold in the last 200 years - there's no reason why this increase cannot continue, because as well as our capacity to labour, we also all have a tremendous capacity to think, to use our brains to solve the problems that living together on our planet present to us.7 billion people means 7 billion minds that could be applied to solving the problems that collectively face our species.

The resources are there, if we have the wit and the will to release them. Just cutting the amount that the world spends on arms by 25% would mean we could feed, house, clothe, educate and provide healthcare to every single individual on this planet to the highest standards. The problem really is not too many humans, the problem is too little humanity.

Two of the key skills we'll need to cultivate if we are to find ways to generate creativity, accelerate our productivity, redistribute our resources fairly, is firstly the capacity we have to listen well to each other, and secondly the capacity to think respectfully together, across the boundaries of language, culture and traditional enmities. The UN campaign '7 billion actions' gives us the tiniest taste of the kind of things we could achieve through such consistent mindful dialogue.

What will motivate us toward such change? As well as our 7 billion minds and our 14 billion hands, we have 7 billion hearts. Human beings have evolved as social animals, that have cared for each other and held our communities together through bonds of love and duty to each other, let's also cultivate our hearts, our compassion for each other and our will to achieve dialogue, justice and peace among our 7 billion strong family.

It's been suggested that the rise in the human population is a big problem, a whole host of neo-Malthusians are lining up to suggest that this many people inhabiting our globe can only be a bad thing, to demand programmes of 'humane population control' and to suppress this human urge to procreate ourselves.

We must not confuse a wish to get rid of poverty with a wish to get rid of the poor. We need to reject a fearful view of our own species. Trying to artificially supress reproduction is deeply damaging to society, as the experience of India and it's transistor radios, or China and it's one child programme shows anyone who cares to look.

Despite the scaremongering, there are ample world resources, if we're prepared to think together of ways to use them less wastefully and more efficiently and fairly, and in tune with our environment.

Every human being is another set of hands ready to work productively for our world community, and our productivity has gone up at least 11 fold in the last 200 years - there's no reason why this increase cannot continue, because as well as our capacity to labour, we also all have a tremendous capacity to think, to use our brains to solve the problems that living together on our planet present to us.7 billion people means 7 billion minds that could be applied to solving the problems that collectively face our species.

The resources are there, if we have the wit and the will to release them. Just cutting the amount that the world spends on arms by 25% would mean we could feed, house, clothe, educate and provide healthcare to every single individual on this planet to the highest standards. The problem really is not too many humans, the problem is too little humanity.

Two of the key skills we'll need to cultivate if we are to find ways to generate creativity, accelerate our productivity, redistribute our resources fairly, is firstly the capacity we have to listen well to each other, and secondly the capacity to think respectfully together, across the boundaries of language, culture and traditional enmities. The UN campaign '7 billion actions' gives us the tiniest taste of the kind of things we could achieve through such consistent mindful dialogue.

What will motivate us toward such change? As well as our 7 billion minds and our 14 billion hands, we have 7 billion hearts. Human beings have evolved as social animals, that have cared for each other and held our communities together through bonds of love and duty to each other, let's also cultivate our hearts, our compassion for each other and our will to achieve dialogue, justice and peace among our 7 billion strong family.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)